In this overview, we analyze some of the most famous crisis management cases in history. We do so critically, searching for common patterns and recurring themes. In the final section, we summarize our findings and outline general principles.

Crisis Management in marketing and corporate communications describes a process-based approach using strategies to identify and respond to threats, unforeseen events, and reputation crises that could potentially cause lasting damage to a brand and destroy sales.

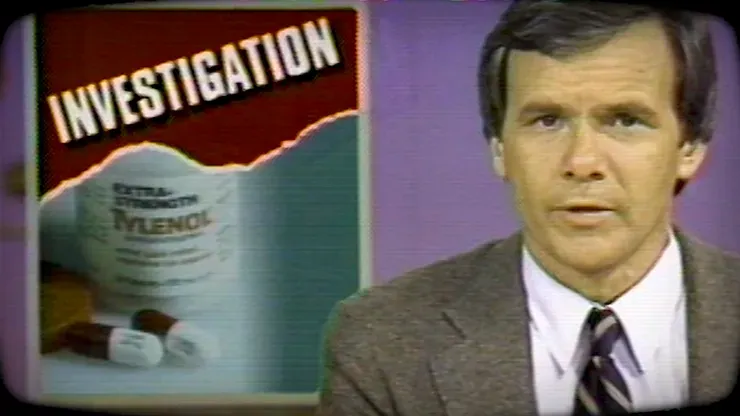

Johnson & Johnson During the Tylenol Tampering Crisis - 1982

September 29, 1982. We are in Chicago, in a quiet American suburb. Mary Kellerman has a common cold: a bit of a sore throat, a runny nose, muscle aches. One of those ailments easily resolved with rest and some acetaminophen when needed. In the middle of the night, her mother is awakened by the child's complaints. There is an unopened package of Tylenol in the house. A single dose of the medication would have been enough to bring the temperature down and ease the discomfort.

An altogether ordinary episode, a slice of everyday life, that marks the beginning of a series of tragic deaths. Mary would die after taking the medication, at 7 in the morning. And from that moment, the deaths followed one after another.

News of the deaths began to circulate. On September 30, 1982, a call from a Chicago Tribune reporter marked the beginning of a flood of information requests to J&J that reached staggering numbers, in the thousands. Investigations by the authorities provided an answer: potassium cyanide poisoning.

The company's reputation was at stake. The potential damage to its image was enormous. They had to act quickly. And effectively. Action was needed on two fronts: preventing further poisonings and restoring the company's good reputation.

A massive communication and organizational effort was launched with the goal of recalling all Tylenol packages from the market.

- Communication to industry professionals, including medical staff and pharmacists;

- Establishment of a dedicated toll-free number for reporting emergencies and addressing all public concerns;

- Recall of millions of packages.

Once the acute phase of the emergency had passed, the next step was to regain consumer trust. People were in a state of shock, experiencing a form of collective post-traumatic stress.

No one could guarantee that such incidents would not happen again. There was now a precedent.

Unless tampering could be made impossible. The technical staff had a brilliant idea: design a tamper-proof package.

It was a success. And we are not the ones saying it. The numbers speak for themselves: in just 5 months, the recovery was remarkable, reaching 70% of the original market share. After just a few more months, that figure reached 98%. A true miracle, made possible only through a crisis management operation that borders on the incredible. Flawless execution and speed were the two fundamental ingredients in managing this crisis.

British Petroleum During the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill in 2010

April 20, 2010. We are 52 miles southeast of Venice, Louisiana. The Deepwater Horizon offshore mobile drilling unit explodes, burns, and sinks in the Gulf of Mexico.

The economic, environmental, and human toll was nightmarish. Eleven of the 126 workers on the platform were killed, and a staggering 3.19 million barrels of oil spilled into the Gulf of Mexico.

To put this in perspective: just over 20 years earlier, the Exxon Valdez tanker had spilled approximately 257,000 barrels of oil in Alaska. The largest tanker disaster in history up to that point was roughly 12 times less severe by comparison.

Images of the catastrophe began circulating rapidly. And they made history.

The enduring symbol of the tragedy, seared into collective memory, are the photographs of pelicans completely coated in oil. Their plumage had turned pitch black. Their original coloring was unrecognizable.

These images represented not only the environmental damage to marine species but humanity's failure to protect animal life and biological ecosystems.

The episode was of epochal proportions. Unimaginable. And equally unimaginable was the potential economic and reputational damage to the company.

But as we saw with the Tylenol case, even in the face of the worst tragedy, the worst outcome can be avoided with an effective crisis management strategy.

However, our second story does not have a happy ending. Quite the opposite -- it is a failure across the board. But every cloud has a silver lining. And from the worst situations, we can draw lessons on how not to manage a crisis.

Analyzing the Key Mistakes

The first mistake was the lack of leadership.

When situations like these occur, coordination is essential: the corporate group must act as a cohesive, synchronized unit.

In this regard, the response was dismal. And the data proves it: following the disaster, several gas stations affiliated with the company ended up changing their names. They did not want to be associated with the company in any way. Understandable, all things considered.

It is difficult to say whether effective leadership could have prevented this collective desertion. But the absence of a top-down action plan certainly did not help.

Second mistake: being completely unprepared to manage the situation on the ground. Oil flowed freely for weeks with no containment whatsoever. In fact, the company made no serious attempt to contain it. For a company of this scale, properly managing an emergency of this type should be the top priority. And it is not even difficult to foresee that a tanker could sink due to a malfunction or human error. It is almost intuitive.

What seems obvious to us today was not apparent to upper management. Or, more likely, the scenario had been considered but deemed extreme: a statistically negligible probability of occurrence. However, we are dealing with events and disasters that do not follow linear trajectories. When the potential for ecological catastrophes of epochal proportions is at stake, policies based on statistical risk calculations are largely inadequate. This story is a glaring demonstration of that.

The company's policies in the years leading up to the disaster are illustrative of its overall approach.

To cut costs, management had implemented a series of cuts to key departments critical for managing such emergencies.

- Communication spending with the government and the public relations budget: more intensive dialogue with government bodies would have enabled not only better coordination on the ground but also more effective communication with the public;

- Cuts to the risk management department: a lack of budget coupled with a total absence of crisis management frameworks.

Third factor: the lack of effective communication.

This is perhaps the most serious and significant error.

At the center of our analysis is an interview with the company's CEO: Anthony Bryan Hayward.

He stated: "There's no one who wants this thing over more than I do. You know, I'd like my life back."

Anthony Bryan Hayward's focus, at such a delicate moment of crisis, was inward: his life, his person, his career. In the face of a catastrophe of epochal proportions that had caused thousands upon thousands of victims -- both human and animal -- leading to an unprecedented ecological disaster, focusing on one's own life and the consequences for one's own career was an inexcusable mistake.

The consequences? A series of fines in the tens of billions of dollars, imposed by the United States government.

And, above all, the loss of consumer trust.

The company ultimately survived only after a series of restructurings and cutbacks. It never returned to its former state.

Apple's Response to the iPhone 4 Antenna Issue - 2010

Let us now jump forward on our timeline. It is 2010. Steve Jobs is still CEO of Apple. Revenue is soaring. A great year for the company, marked by the release of a new model: the iPhone 4.

Long lines form outside Apple stores and retail locations. Excited customers show off their purchases. But this launch is unlike all the others.

Before long, something very strange emerges: the phone loses network connectivity. And that is not all. When the phone is held in the left hand, calls drop.

This is the beginning of Antenna Gate. The beginning of one of the most celebrated crisis communication cases.

Steve Jobs is on vacation in Hawaii at the time of the incident.

He cuts his vacation short immediately. What follows is the preparation of a press conference, which opens with a sarcastic, provocative, brilliant video. The tension is diffused with extraordinary wit: "There is no Antennagate." A statement that essentially defines Apple's and its founder's approach to the situation.

The conference opens with nothing less than a sarcastic song taken from YouTube.

Instead of minimizing the risk, instead of attempting a futile exercise in denial, Steve Jobs candidly admits that Apple phones are not perfect, and they are not unique. Like all phones, they can have problems. And this admission comes from a company that has always claimed to be ahead of the competition. And that, in many ways, was and still is.

From this point on, Steve Jobs adopts a deeply pragmatic approach.

Using data and objective figures, he demonstrates that the situation in terms of customer service, call volume, and returned phones was not that serious. None of these three metrics had shown a spike.

However, this does not serve as an excuse. Steve Jobs immediately commits to ensuring maximum quality so that every user is deeply satisfied. And in the meantime, before finding a solution, all users were offered a completely free iPhone 4 case.

The results of this masterful communication strategy are plain for all to see: trust in the brand was restored, the company did not experience a decline in sales, and Apple's image actually emerged stronger.

Can we emulate Steve Jobs? No.

Can we draw inspiration from his use of data and rationalization? Yes.

Chipotle Mexican Grill and the Salmonella Outbreak

The well-known Mexican fast-food chain, with 2,000 restaurants worldwide, was hit in 2015 by a salmonella outbreak. It spread across 14 states with alarming speed and severity. At its peak, 88 people were infected.

A media firestorm erupted, and swift action was needed on two fronts: restoring consumer trust and preventing further deterioration of the epidemiological situation.

First, the closure of multiple restaurants was ordered. Perhaps even more than strictly necessary. This signaled to the public a sense of caution and, above all, a willingness not to take the issue lightly.

Next, a comprehensive review of safety procedures and testing protocols was launched, dramatically tightening inspection standards. These practical actions were followed by a company press conference, where it was declared that quality control standards were now among the strictest in the industry.

The emergency situation was contained. But one final piece was still missing: restoring trust in the brand.

And, as we saw in the Apple case, when sales decline due to an emergency, the best way to regain consumer trust is sometimes to offer vouchers, promotions, and coupons.

Bring people back into the fold of your business to reassure them. The more you use a product, the more familiar it becomes, the more positive your opinion grows.

Another example of excellent market crisis management.

Target's Data Breach

Between November 27 and December 18, 2013, one of the most notorious cyberattacks in history occurred, targeting the retail chain Target.

The scale was staggering, especially by the standards of the time: 40 million credit card numbers stolen, 70 million customers affected. But the attack did not just involve credit card data. It also compromised PINs, customer names, email addresses, phone numbers, expiration dates, and security codes.

Applying a method we have already used in analyzing other cases, let us focus here on the official statements to assess the effectiveness of the communication strategy.

First statement from the CEO:

"Yesterday we shared that there was unauthorized access to payment card data at our U.S. stores. The issue has been identified and eliminated. We recognize this has been confusing and disruptive during an already busy holiday season. Our guests' trust is a top priority at Target and we are committed to making this right. We want our guests to understand that just because they shopped at Target during the impacted time frame does not mean they are victims of fraud. In fact, in other similar situations, actual fraud has been quite low. Most importantly, we want to reassure guests that they will not be held financially responsible for any credit and debit card fraud. To provide guests with extra assurance, we will be offering free credit monitoring services. We will be in touch with those who have been impacted by this issue soon on how and where to access this service."

On its own, this is not a bad start. Of course, we are far from Steve Jobs' brilliance during Antenna Gate. And a less formal approach would have been preferable. But overall, the message is clear, concise, and leaves no room for misunderstanding.

What comes next, however, is unconvincing:

"We take this crime seriously. It was a crime against Target, our team members, and our guests. We're in this together and, in that spirit, we are extending a 10% discount -- the same amount our team members receive -- to guests who shop in U.S. stores on December 21 and 22."

What stands out? Remember the Deepwater case? What do they have in common?

Exactly: the order of priorities, the inward focus. In the face of an emergency like this, you cannot list the company first and then the team. This is no small detail. These nuances make the difference between a good and a bad crisis management strategy.

The customer must feel reassured. They must sense that they are the center of attention, that you are working to solve their problem at that moment. In the communication framework, they must have the leading role.

But what about the operational side? A disaster. Of epic proportions.

First mistake: letting more than a day pass from the moment of the emergency before releasing a communication.

This violates another rule we have seen consistently in all successful cases. A rule that can be summarized as: "the bigger the disaster, the faster the communication must be."

Second mistake: a lack of organization in handling incoming requests. If you are a company of that stature, you cannot afford to be disorganized. You must be able to handle every external request that comes your way. Volume is no excuse.

And in this regard too, the response was extremely poor. The staff proved incapable of managing the volume of incoming calls. Once again: if you try to save on your risk management budget, you will pay the consequences later.

The Rogue Employees at Domino's Pizza

Remember the scene from Fight Club where Tyler is described as a guerrilla terrorist in the restaurant industry? Where our co-protagonist is shown urinating in the lobster bisque?

Well, reality sometimes surpasses fiction. Something similar happened in 2009. Had it occurred just 10 years earlier, the whole thing would have amounted to a simple case of food poisoning. Perhaps one fewer customer, but nothing capable of compromising the reputation of such a well-known brand. But it is 2009, and in the age of the internet, a mistake like this can be very costly. Especially when the employees themselves have the brilliant idea of filming themselves engaging in decidedly "unhygienic" practices with the sandwiches.

We are talking about the Domino's Pizza scandal.

The footage began circulating at a disarming pace. Within hours, it reached 1 million views. Videos showing employees of the well-known fast-food chain stuffing pieces of cheese up their noses, sneezing on food, and passing gas on slices of salami.

The case had all the potential to permanently destroy the company's reputation. And if that did not happen, it was once again thanks to an effective crisis management strategy.

Domino's Strategy

As we have seen in previous case studies, one of the determining factors is speed.

It is not enough to react well. You must also react quickly. And the importance of speed in this incident manifests both negatively and positively.

On the discovery side, the response time was lightning fast. Thanks to a fan, the company found out about the video almost immediately and gained precious time -- time needed to take all necessary measures.

The company immediately contacted YouTube to have the video removed. Then it identified the employees involved and took the necessary legal action. In record time.

There is a caveat, though: it all happened behind the scenes. The company attempted a cover-up. And this is one of the flaws in this strategy. Domino's should have immediately released a public statement (note the connection to the Target case).

But fortunately, they corrected course quickly. Shortly after, on Twitter, they tried to reassure the public: it had been an isolated incident. All necessary measures were being taken, including termination. Such incidents would not happen again.

Technology takes, and technology gives. By skillfully leveraging the power of information sharing, the company asked its followers to retweet the message to reach the widest possible audience.

And once again, a video saved the company's reputation. This time, it is the company's president himself, Patrick Doyle, who speaks. Calmly but assertively, he channels his outrage over the incident, reaffirms that this is a tragedy for everyone, and thanks the web for its feedback.

When a CEO puts themselves out there like this, fans appreciate it.

Proof of this communication strategy's effectiveness? Well, let us once again let the numbers speak: from 2009 to 2023, the company's stock price rose from $9 to $350. We can safely say that the impact was ultimately limited in duration.

Conclusion

We have analyzed several crisis management cases, each with its own specific characteristics.

But we have also seen how, despite their differences, they share a series of recurring patterns. Here are the best strategies for when you are facing reputational destruction and need an outstanding crisis communication strategy:

- Pre-established risk management strategies, designed before any event occurs, for handling "black swans";

- Leadership capable of ensuring coordination and effective allocation of available resources to resolve the emergency;

- Prompt and effective communication with your audience, both during and after the emergency;

- Empathetic communication directed outward (customers, the public) rather than inward (team, company);

- Implementation of commercial strategies (such as offering vouchers or discounts) after the emergency to strengthen the bond with the brand.

Obviously, this is not a perfect "Bible." Every case has a life of its own. But these generalizations can serve as a universal framework for avoiding glaring mistakes and the destruction of brand equity and market trust.